Talk of the Town

I.

On February 15, 1926, the Philadelphia bookseller A.S.W. Rosenbach bought the Melk abbey copy of the Gutenberg Bible at auction at Anderson Galleries in New York City. The sale made the papers around the world. The San Bernardino Sun reported that the "opening bid was $50,000, and bidding lasted about ten minutes."[1] In New Zealand, the Dunstan Times reported that some 2000 people attended the sale, bidding begun by Belle DaCosta Greene, librarian for J. Pierpont Morgan; the sale price of $106,000 was "the highest price ever paid for a book."[2] Meanwhile, "Guppy," or Dr. Henry Guppy of the John Rylands Library in Manchester, England, found the sale price to be "preposterous," sniping to The New York Times that a far more reasonable figure would have been $25,000, and that the copy "is not even on vellum."[3]

A month later, the sale was still news in "Talk of the Town," in the March 27, 1926 issue of The New Yorker:

When the Melk copy of the Guttenberg [sic] Bible, enjoying as it deserved, a catalogue all by itself, was finally knocked down to Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach for the tidy sum of $106,000, many among the legitimately thrilled audience wondered who the distinguished looking white-haired gentleman was who joined the bidding in the eighty thousands and pursued the indefatigable Dr. Rosenbach as far as $105,000.[4]

The unlucky underbidder had been hoping to secure the Gutenberg Bible for the new Cathedral of St. John the Divine, the largest cathedral in the world, still being built on the west side of Morningside Heights in Upper Manhattan.

II.

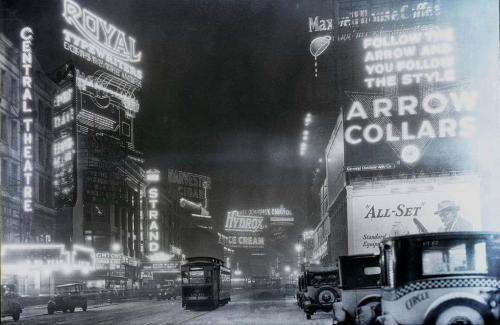

That week's The New Yorker highlighted another event in Manhattan: the Broadway production of "The Great Gatsby," adapted for the stage by Owen Davis from F. Scott Fitzgerald's novel, published to lackluster sales the year before. The play had opened in January at the Playhouse in Great Neck, Long Island; in February, it moved to the Ambassador Theatre, then five years old, at 49th Street and Broadway.

In Davis's adaptation, two of the three acts are set in Gatsby's library, in his house in West Egg, Fitzgerald's fictional rendition of a wealthy enclave on the North Shore of Long Island. Readers of the novel will remember Gatsby's library: wandering through the chaos of a house-party to find their host, Nick and Jordan unwittingly discover it. "On a chance we tried an important-looking door, and walked into a high Gothic library, paneled with carved English oak, and probably transported complete from some ruin overseas." Here they find a stranger, in "owl-eyed spectacles," peering tipsily at the bookshelves:

As Fitzgerald knew, Stoddard’s Lectures was a fifteen-volume, popular and inexpensively produced set of travel lectures by the late nineteenth-century American theologian, John Lawson Stoddard. Even uncut (and therefore only ever at best partially read), the volumes would have been mass-produced, of poor quality, of precisely the cardboard that Owl Eyes expects.[6] Equally, the Belasco of Owl Eye’s description was David Belasco, an American theatre director in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. To be a “regular Belasco,” as Fitzgerald knew, was to be authentically inauthentic. As Kevin Dettmar observes, the point of Gatsby’s library is to be a “library”: “a simulacrum of some recognized token of cultural attainment.”[7]

On Broadway, Gatsby died in his library, shot in front of his onlookers, surrounded by staged books. The library might simply have been a dramatically coherent space, and one easier to stage than, for instance, the swimming pool in which Fitzgerald had Gatsby’s body discovered, floating on a pneumatic mattress. But the library, and its real or unreal books, was also a space that could make visible a particular strain of anxiety, one easily recognizable to a Broadway audience.

III.

“A new world, material without being real, where poor ghosts, breathing dreams like air, drifted fortuitously about,” Fitzgerald wrote of Gatsby’s last moments. The real book, and the realness of books, were issues of enormous significance to a generation of Americans from the late nineteenth century. In 1910, Charles William Eliot, retired President of Harvard College, edited the “five-foot shelf,” or Harvard Universal Classics. The fifty-one volumes, in uniform cloth publisher’s binding, occupied a particular five feet in the fireside bookshelves of American living rooms—and childhoods—through the twentieth century.[8] Here was reading as the very bootstraps of moral aspiration and duty, in Eliot’s “portable university,” with its “picture of the progress of the human race within historical times.”[9]

The Gutenberg Bible also came to represent the "progress of the human race," and perhaps to epitomize the new location of this progress in the United States. From the mid-nineteenth century, the Gutenberg Bible became a particular focus for wealthy American collectors. In 1900, a survey of New York collections could describe no fewer than six copies, their genealogies elaborated like those of racehorses. The Gutenberg Bible’s importance was assumed: of one of the copies owned by Robert Hoe, the author observes that it was “an extraordinary copy of an extraordinary book, the first book ever printed and the glory of Gutenberg.”[10]

The particular reasons for this importance were less coherently articulated. Like the Harvard Universal Classics, the Gutenberg Bible was presented as a symbol of progress: as the first printed book, and the marker of a specific moment of transition from the archaic to the modern. It was also understood as a work of particular beauty, praised for the quality of the ink, the paper, the symmetry of the printing. For American private collectors in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the Gutenberg Bible was taken as a work of peculiar rarity and value, one whose acquisition by American collectors marked the new significance of American collections, and a vision of America's role in shaping human progress in a new era. As Fitzgerald wrote, "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past."

Notes